When you spend tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars to install an elevator, the last thing you want is to regret your choice. Think about it: after the elevator is installed, if it runs slowly, is very noisy, or is very expensive to run, and only then you realize you chose the wrong type, that would feel terrible.

If you are unsure between a hydraulic elevator and a traction elevator, please keep reading. This article will help you weigh the pros and cons and choose the elevator type that really fits your needs, not just the one that looks cheapest on the quote.

Traction Elevator vs Hydraulic Elevator: What Is the Difference?

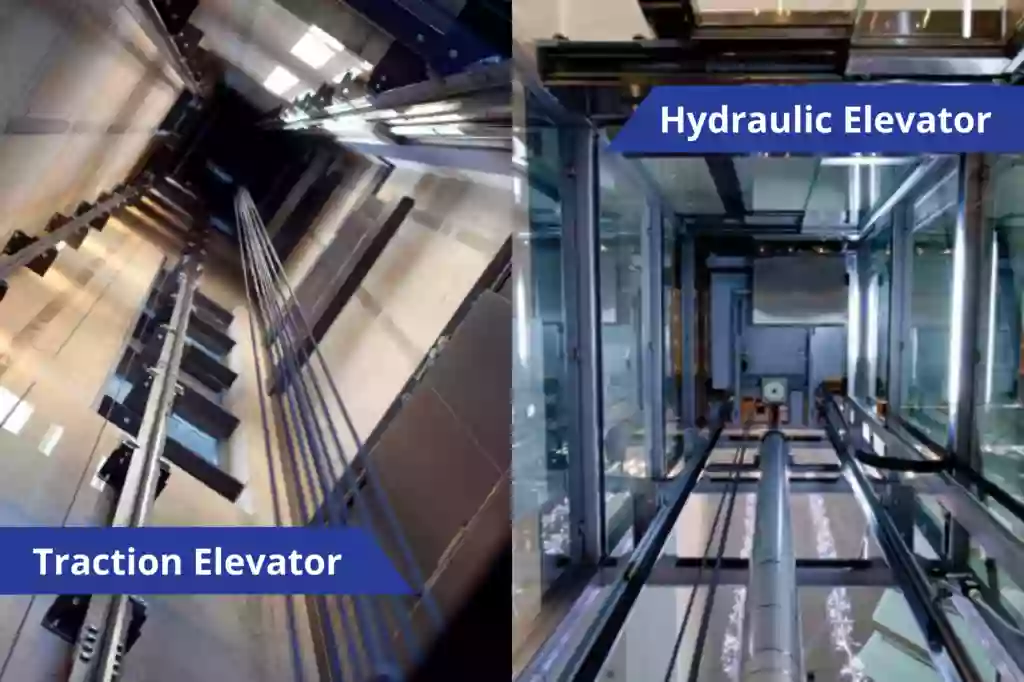

Traction Elevator

A traction elevator is an elevator where the car hangs on steel ropes or steel belts and is pulled by an electric motor and a counterweight.

It runs inside a concrete or steel shaft and usually needs more headroom at the top and a deeper pit at the bottom. This type of elevator is designed for daily use in residential and commercial buildings. Even when the building gets taller and the number of users increases, it can still stay efficient and comfortable.

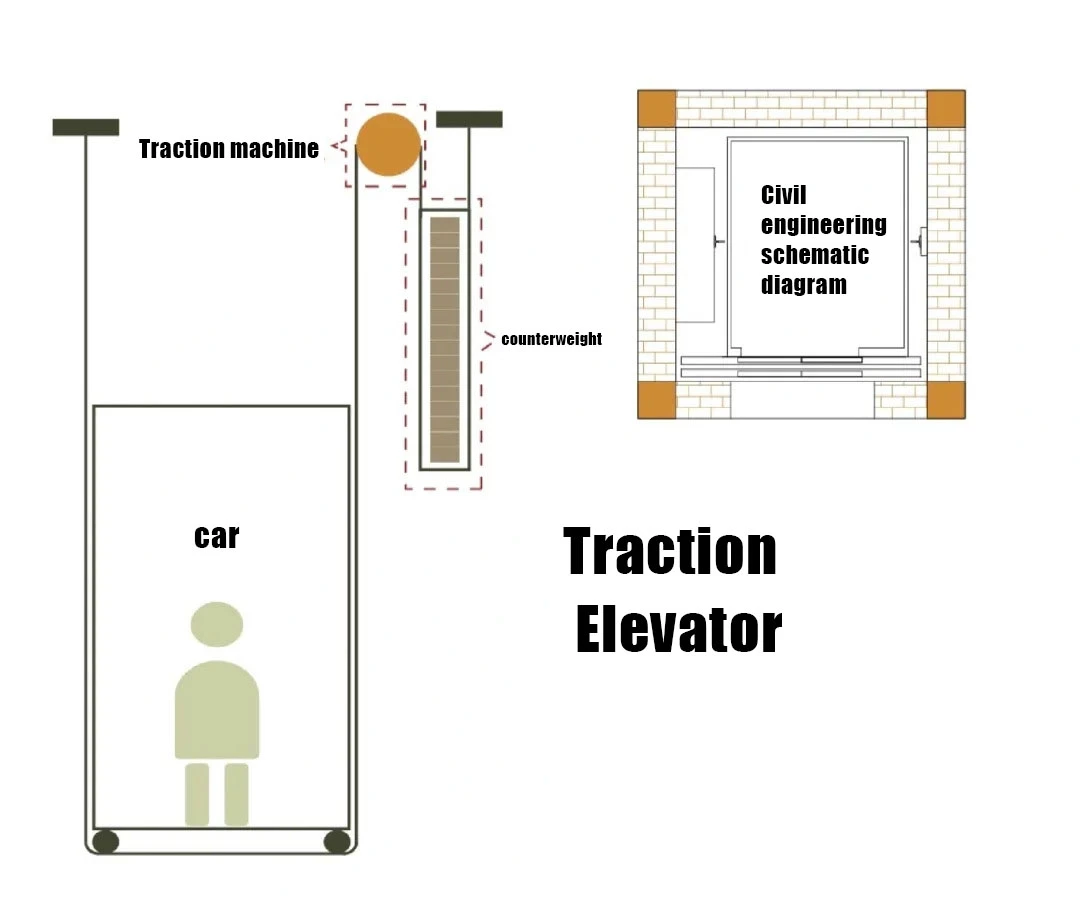

Hydraulic Elevator

A hydraulic elevator is an elevator that uses a piston and hydraulic oil to push the car up from below, instead of hanging the car on ropes and a counterweight like a traditional elevator.

The pump unit is usually installed in a small machine room near the lowest floor, and the required headroom in the shaft is lower. This is helpful for buildings with limited space or for upgrading existing buildings. Hydraulic elevators are mainly used in low-rise projects with fewer floors and less traffic. In these projects, budget and building limits are more important than speed.

The Main Difference Between Traction Elevators and Hydraulic Elevators Is:

a traction elevator uses steel ropes or belts plus a counterweight, and is designed for mid- and high-rise buildings with frequent daily use. Its initial installation cost is a bit higher, but it saves more energy and gives a better ride.

A hydraulic elevator uses a cylinder and oil pushing up from below, and is designed for low-rise, space-limited projects. The building structure requirements are more relaxed and the first quote looks better, but its speed is limited, and its energy use and later maintenance pressure are higher.

|

|

|

Traction Elevator vs Hydraulic Elevator: Which Is Better?

If the main focus of the project is ride comfort, speed, and long-term energy use, especially for residential, office, or hotel buildings with more than five floors and high daily use, a traction elevator is usually the better choice. In these cases, a traction system can provide higher speed, smoother starting and stopping, and more controllable power use under proper shaft conditions. This gives a better overall user experience and better operating cost control for the property and the owner.

But this does not mean a hydraulic elevator can be simply ruled out.

In projects with fewer floors (usually two to three), limited building conditions, or very sensitive renovation cost, a hydraulic elevator can have clear advantages. It has more relaxed requirements for headroom and pit depth. The equipment price and installation work are usually lower. It is suitable for villas, small commercial buildings, and existing buildings where an elevator is added later. In these projects, the elevator makes fewer trips each day, and the energy difference will not grow very large. The key question is often whether the elevator can be installed within the existing building conditions and an acceptable budget.

In short, in new multi-storey residential buildings, office buildings, and public or commercial buildings with more than five floors, traction elevators are overall better in performance, energy use, and long-term value, and should be the first choice. In low-rise buildings and space-limited projects, when building structure limits and budget limits are stronger, a hydraulic elevator with proper design and selection is still a workable solution.

Traction Elevator vs Hydraulic Elevator: How to Choose?

In real projects, choosing a traction elevator or a hydraulic elevator usually means looking at use, number of floors, traffic level, building conditions, budget, and operation period at the same time. When you start from these questions, the choice often becomes clear.

-

First, Be Clear About Use and Use Level

The first step in choosing an elevator is to be clear about who the elevator will serve and how often it will run. For example, is it a normal passenger elevator in a residential building, a public elevator in an office building, or an extra elevator in a villa or a small commercial building? For buildings with two to three floors and few trips per day, a hydraulic elevator can meet basic comfort needs and at the same time lower equipment and installation cost. The running load is light, and the difference in energy use is not big.

When the building has more floors and more passengers, the advantages of a traction elevator become stronger in running speed, ride comfort, and waiting time control. For small high-rise residential buildings, office buildings, hotels, and hospitals, traction elevators fit better for high-frequency use and help reduce crowding and complaints.

-

Then, Compare Building Conditions and Space Limits

When choosing an elevator, you need to carefully check shaft size, headroom at the top, pit depth at the bottom, and machine room conditions. A traction elevator has certain needs for headroom and pit depth and is more suitable for new projects where you can plan with the building structure and reserve the right conditions from the start. If you are adding an elevator to an existing building and the top floor height is not enough or the foundation is hard to deepen, using a traction plan may need large structural changes. However, there are also MRL (machine-room-less) traction elevators. This type has lower needs for separate machine room space and pit depth. If you now have an add-on or space-limited project, you can look further at our MRL traction elevator.

Hydraulic elevators are more flexible in this area. Their needs for headroom and pit depth are usually more relaxed. In old buildings, villas, or partial renovation projects, if the original structure is limited, a hydraulic elevator can often be installed with less structural change. This helps reduce the impact on the original building and its use.

-

At the Same Time, Look at Budget and Whole Life-Cycle Cost

Budget is one of the key factors in most projects. For the first cost of equipment and installation, hydraulic elevators in low-rise buildings usually have an advantage in price and fit projects with high pressure on one-time investment. But an elevator is a long-term device, and you need to look at energy use and maintenance cost over its whole life.

Because traction elevators use a counterweight to balance the car, the power used per trip is usually lower than that of a hydraulic system in the same conditions, especially in buildings with many trips per day. The long-term energy difference can be clear. A hydraulic elevator needs the pump station to provide all the lifting force every time it goes up. This makes control of oil temperature, valves, and system condition more important. When you decide, it is better to compare both the first cost and the estimated 10–15 years of running and maintenance cost, not just the equipment price.

-

Think About Construction Work and Coordination Difficulty

For new projects, traction elevators join the design stage early and are coordinated with architecture, structure, and MEP. The overall fit is good and helps later stable and comfortable operation. For existing building renovation, where the elevator position is limited or there are many pipes and cables, the flexibility of hydraulic elevators in equipment layout and building needs can sometimes clearly reduce structural work, shorten the construction period, and reduce the impact on residents or business.

In new multi-storey and mid- to high-rise residential buildings, office buildings, and public buildings, if there are no special structure limits, traction elevators are usually better in performance, energy use, and long-term value and should be chosen first. In buildings with fewer floors, limited space conditions, or added elevators in existing buildings, if the space for building changes is small and the first budget is tight, a hydraulic elevator with proper design and risk study is a mature and cost-effective option. By looking at use, use level, building conditions, budget, and operation period together, you can usually reach a clear choice.

Is a Hydraulic Elevator Cheaper Than a Traction Elevator?

If you only look at the one-time cost of buying and installing the elevator, then in most markets, the quote for a hydraulic elevator is usually lower than for a traction elevator with the same rating. This is also why many villas, small commercial buildings, or old building add-on projects first receive a hydraulic plan: with a limited budget, it is easier to “get the elevator built”.

You need to note that this “cheaper” mainly means equipment price plus installation cost, and usually only in cases with few floors, low speed, and basic configuration. When the number of floors goes up, speed increases, and the needs for noise control and comfort rise, the cost of the hydraulic system itself also goes up. At that time, the price gap between hydraulic and traction becomes much smaller.

At the same time, you should not simply think that a traction elevator is always more expensive. In some projects, if a traction elevator uses a standard MRL model with medium configuration, and the hydraulic plan needs extra sound insulation, cooling, or special building work, the total price difference between the two plans may not be large, and sometimes the traction plan can even have an advantage. So before making a decision, a safer way is: under the same project conditions, ask suppliers to give detailed configurations and total prices for both hydraulic and traction plans, and compare them side by side.

More importantly, price judgment should not stop at the first investment. When a hydraulic elevator runs, every time it goes up, the pump station must provide all the lifting force. Over time, energy use and oil system maintenance cost can be higher. A traction elevator uses a counterweight to balance the load, and over ten or more years, the electricity bill and the cost of changing key parts are usually more controllable. For buildings that will be held for a long time and have high use frequency, even if the first cost of a traction elevator is a bit higher, the total cost over its life is often not higher and may even be lower.

|

|

|

Are Cab Sizes the Same in Hydraulic and Traction Elevators?

In most cases, under the same rated load and the same shaft clear size, the cab sizes of hydraulic elevators and traction elevators are basically at the same level. How big the cab can be mainly depends on the rated load, code needs (such as space for wheelchairs or stretchers), and shaft clear width and depth, not on whether the elevator is “hydraulic” or “traction”.

For example, for a common 630 kg (about 8-person) passenger elevator in a standard shaft, whether it is hydraulic or traction, the cab inner size is usually about 1.1–1.4 m wide and 1.3–1.4 m deep. The differences between plans are mostly small changes of a few dozen millimeters up to about one hundred millimeters, not “one much larger and one much smaller”.

You need to pay special attention that what affects usable cab area is the shaft layout:

Some hydraulic plans use a side-mounted cylinder, which takes some shaft width.

Some traction plans place the counterweight on the side or at the back, which also affects how well the shaft is used.

So size differences usually come from layout and product design, not from the drive type itself.

If your project is very sensitive to cab inner size and door width, the better way is: under a fixed shaft size, ask manufacturers to provide floor plans for both hydraulic and traction plans, compare the usable cab width and depth under the same shaft conditions, and do not assume “hydraulic is always smaller” or “traction is always bigger”.