You may walk into an elevator, press a button, and forget about it a few seconds later. But if you stop and think, it is a strange experience: you stand in a metal room, it moves up and down with you inside, and you trust it completely.

That trust brings up some questions worth thinking about:

-

What is really holding the elevator up?

-

If something goes wrong, what stops it from falling?

-

What if the power goes out while you are inside?

-

Why do some elevators feel smooth and quiet, while others shake and bump?

This guide will walk you step by step through how modern elevators really work.

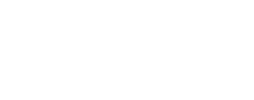

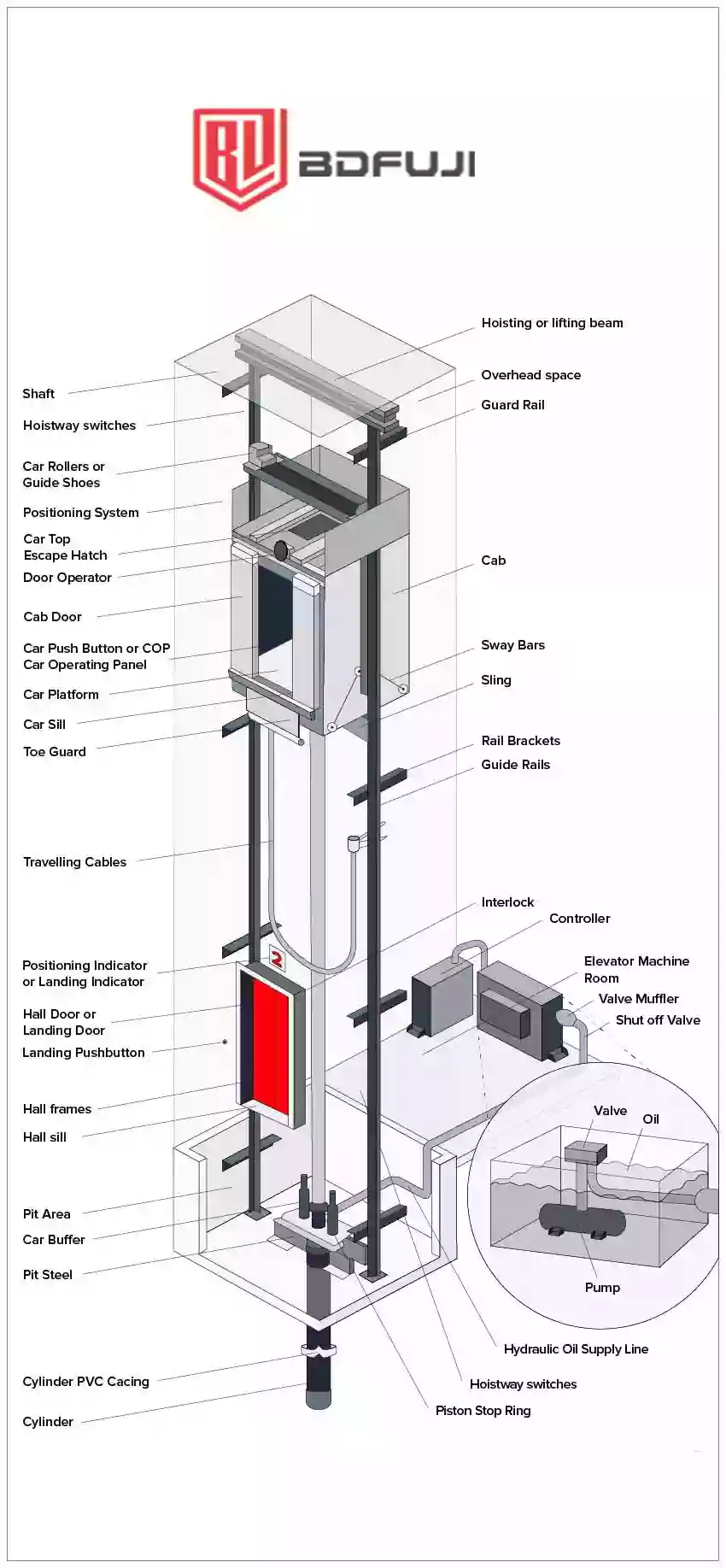

Main Parts of a Modern Elevator System

Before we go into details, it helps to see an elevator as a full system. When you press the button in the lobby and the elevator door opens with a “ding,” many smaller systems are already working together in the background.

A typical traction elevator (the most common type in homes and commercial buildings) has these main parts:

-

Car (elevator cab)

The closed space where passengers stand. It moves up and down, guided by steel rails fixed inside the shaft. -

Counterweight

A heavy block that moves in the opposite direction of the car. It balances most of the car’s weight and part of the rated load, so the motor needs less power and the system uses energy more efficiently. -

Hoistway (shaft)

The vertical space where the car and counterweight move. Inside the shaft, you will see guide rails, landing doors, safety devices, and position marks used by the control system. -

Suspension system (ropes or belts)

Steel wire ropes or coated steel belts loop around the drive sheave (pulley). One end connects to the car, and the other end connects to the counterweight. They pass the machine’s pulling force to the car and counterweight. -

Machine (traction machine or drive unit)

Made of a motor, a drive wheel, and a brake. The motor turns the drive wheel; friction between the ropes and the drive wheel moves the car and counterweight. When the elevator stops, the brake holds the system still. -

Controller (control panel)

The electronic “control system” receives button signals, chooses the next floor to serve, controls motor speed and direction, and watches all safety circuits. -

Door system

Each floor has a landing door, and the car has a car door. The door operator in the car opens and closes the doors, and mechanical interlocks make sure the landing door can open only when the car is correctly parked at that floor. -

Safety devices

Overspeed governor, safety gear, buffers, limit switches, door interlocks, and many safety circuits. These devices watch the elevator all the time, and if anything is abnormal, the elevator stops.

All these parts are carefully designed to work together. The car is not moving “freely.” Its motion is guided by rails, supported by several suspension parts, driven by a controlled motor, and watched by sensors and safety circuits all the time.

In the next section, we start with the question most people care about: what is holding the elevator up, and what stops it from falling?

What Is Really Holding the Elevator Up?

One common fear is simple:

“The elevator is hanging on steel ropes. What if the ropes break?”

To answer this correctly, we need to think about three things: the suspension system, the counterweight, and special mechanical safety devices.

Multiple Steel Ropes

In a standard traction elevator, the car and counterweight are not held by just one rope or one steel belt. They are supported by multiple ropes or belts. Each rope is made from many small steel wires twisted together, and it is designed to carry much more than the real working load.

So, for a well-designed and well-maintained elevator, a “sudden free fall because all ropes break at the same time” is extremely rare. Even if there is a serious rope problem, there is another layer of protection: the safety gear.

Balance System

The elevator car is not hanging alone. On the other side of the ropes, there is a counterweight. When the car goes down, the counterweight goes up. When the car goes up, the counterweight goes down.

So the motor does not need to lift the full weight of a fully loaded car from rest. It mainly works against the weight difference between the car load and the counterweight. This lowers energy use and allows a smaller motor. And because the forces are balanced, the system is more stable and easier to control. The ride is smoother, and it takes less effort to move up or down.

Safety Devices

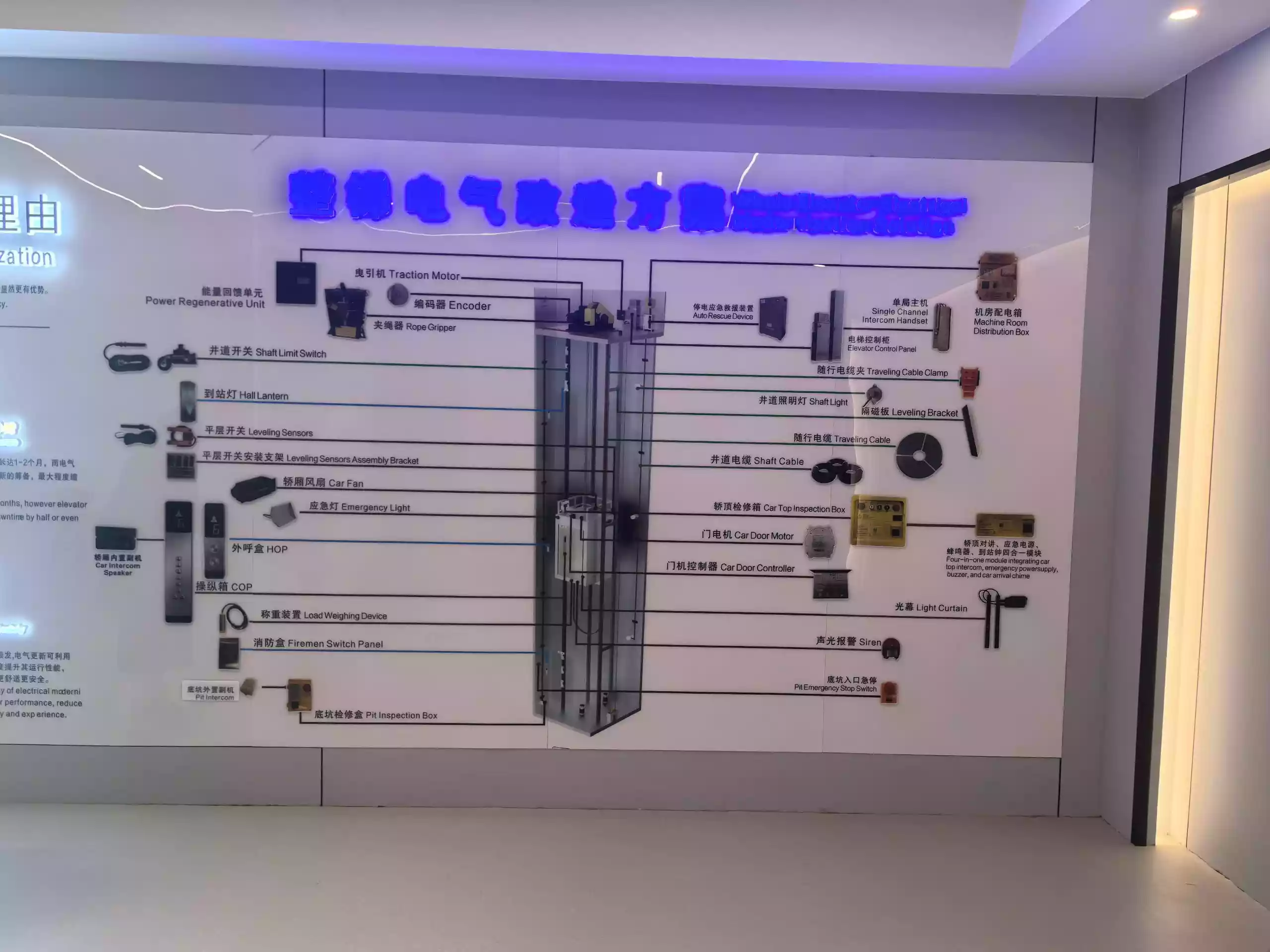

Now we come to the key part: If the elevator’s suspension system or speed has a serious problem, what stops the elevator from moving?This is when the overspeed governor and the safety gear are used:

Modern traction elevators have an overspeed governor and mechanical safety gear fixed to the car. If the car’s downward speed goes above a set limit, the governor trips and activates the safety gear. The safety gear clamps onto the guide rails and stops the car by mechanical force, without needing the motor or electric power.

In short, if the elevator system is installed and maintained to the standard, the chance of an uncontrolled free fall is extremely low.

How Does an Elevator Move Smoothly and Stop Exactly at Your Floor?

The suspension system explains how the car is supported. The next question is how the elevator moves in a controlled way and reaches each floor smoothly.

How an Elevator Moves Smoothly?

In most modern traction elevators, an electric motor (usually a gearless motor with a variable-speed drive) turns the drive wheel. The drive system is not a simple “on” or “off.” It controls:

-

Direction — up or down

-

Speed — how fast the car should move at each moment

-

Torque — how much force the motor must apply, depending on the load

Instead of running a traditional motor at one fixed speed, the elevator drive slowly adjusts the frequency and voltage sent to the motor. This creates a smooth speed curve: start from zero, speed up to rated speed, keep that speed, then slow down to zero as the car reaches the target floor.

That is why, in a well-tuned elevator, you feel a smooth start, almost no feeling during the ride, and a gentle stop at the end.

How the Elevator Knows Its Position?

To run accurately between floors, the controller must always know two things: the car’s position and speed.

Position information is usually collected in two ways. First, an encoder on the motor shaft measures speed and angle, and the traction wheel turns this into car movement. Second, the shaft has reference devices, like magnetic or mechanical switches at each floor, to provide exact alignment points. The controller combines these signals to keep position accurate.

Electricity how landing and accurate leveling?

Accurate leveling is very important for safety and barrier-free access. A well-maintained elevator can stop normally with only a very small height difference between the car floor and the landing.

To do this, when the controller receives a stop command, it calculates the travel distance and creates a motion curve. The drive system then follows this curve by controlling torque and speed. As the car gets close to the landing, the controller lowers the speed based on the curve and watches the feedback.

The final part of the trip is for leveling. The controller makes small adjustments to speed and position so the car floor lines up with the landing threshold, usually within a few millimeters.

Elevator how protect passenger safety?

We already talked about safety gear and the overspeed governor. In fact, modern elevators have multiple independent safety devices. The goal is simple: even if one device fails or detects something abnormal, other safety devices can still protect passengers.

Overspeed Governor

The overspeed governor is mainly connected to the car by a governor rope. In normal operation, it turns at a speed that matches the car speed. If the downward speed goes above a set threshold, the governor trips. When it trips, it mechanically drives the safety gear connected to the car frame.

The safety gear clamps the guide rails and stops the car by friction. This action is mechanical and triggered by speed, so it does not depend on the main control system or the power supply.

Door Protection

The landing door interlock is a key part of the system. The landing doors and the car doors are interlocked. The car can move only when all doors are closed and locked. The safety circuit checks these lock states. If any door is not locked correctly, the circuit opens, and the controller cannot run the car.

At the same time, elevator doors also have devices like light curtains or safety edges to detect people or objects in the doorway. This prevents the doors from closing on them, or tells the doors to reopen.

Other Safety Devices

Modern elevators also have other safety devices, such as:

-

Limit switches that define the allowed travel range in the shaft

-

Final limit switches that stop the car when it gets close to the top or bottom limit

-

Pit buffers that absorb energy if the car reaches the bottom of the shaft at low speed

With regular inspection and maintenance, these devices make the chance of uncontrolled free fall or uncontrolled overspeed very low for code-compliant elevators.

Different Types of Elevators and How They Work

Not all elevators are built the same. The basic safety ideas are similar, but the drive system can be very different. Here are common elevator types and how they work.

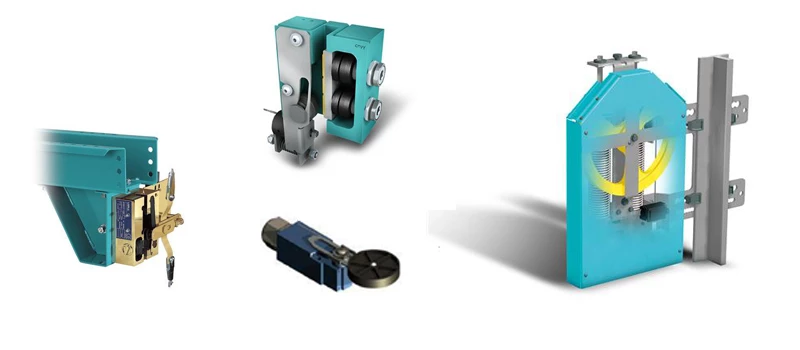

Traction Elevator

Traction elevators are the main solution for mid-rise and high-rise buildings. They use a traction machine, ropes or belts, and a counterweight to move the car.

Main Parts of a Traction Elevator

A typical traction elevator includes:

- Car frame and sling

- Counterweight frame with counterweight blocks

- Steel guide rails for the car and counterweight

- Steel ropes or flat belts connecting the car and counterweight

- Traction machine (motor, traction sheave, and brake)

- Controller and drive unit with encoder and position sensors (VVVF)

- Overspeed governor and mechanical safety gear

The car and counterweight move along guide rails. The ropes pass over the traction sheave, forming a closed loop between them.

How a Traction Elevator Works

The counterweight is sized to balance the empty car and most of the rated load. So the motor only needs enough torque to overcome the unbalanced part of the load and system friction. It does not need to lift the full car mass by itself.

When conditions allow, the controller tells the variable-frequency drive to power the motor. The drive controls the speed curve by slowly changing motor frequency and voltage. As the motor turns, it turns the traction sheave. The ropes sit in grooves on the sheave. The “drive” side and the “return” side have different tension. This tension difference creates a net force, moving the car and counterweight up and down in opposite directions along the rails.

The rope layout changes the relationship between rope speed, car speed, and required force. In a 1:1 roping layout, the car is directly hung by the rope over the sheave, so the car speed equals rope speed.

In a 2:1 roping layout, the rope runs over extra pulleys. The car speed is half the rope speed, but the mechanical advantage is higher.

In high-rise buildings, to balance the rope weight change during travel, compensation ropes or chains are added between the car and the counterweight.

During operation, the motor encoder and shaft landing height sensors keep sending feedback. The controller compares the measured position and speed with the target curve, adjusts the drive output, and manages the final leveling stage so the car floor lines up with the landing threshold within the allowed tolerance.

Safety Features of a Traction Elevator

Traction elevators use many independent safety features:

-

The machine brake on the traction machine is a fail-safe brake. It is held open by electricity when the machine runs, and springs close it when power is lost. If power fails or a fault is detected, the brake closes and holds the sheave to prevent unintended movement.

-

The overspeed governor watches car speed through the governor rope. If the downward speed goes above a set threshold, it trips mechanically and activates the safety gear on the car frame. The safety gear clamps the guide rails and stops the car by friction. This action is independent from the main controller and power supply.

-

Door interlocks make sure the car can move only when all landing doors and the car door are closed and locked. The safety circuit monitors these and other key switches. If any required contact opens, the controller will not allow the car to move.

-

Limit switches define the normal travel range. Final limit switches and buffers protect the extreme positions of the shaft, stopping the car if it goes beyond the normal working area near the top or bottom.

These features work together, so faults usually cause a safe stop, not uncontrolled movement.

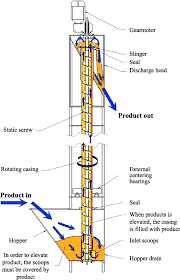

Hydraulic Elevator

Hydraulic elevators are often used in low-rise buildings. These buildings have shorter travel distances and do not need high speeds. They use hydraulic pressure inside a cylinder to push a piston connected to the car.

Main Parts of a Hydraulic Elevator

Common hydraulic elevators usually include:

- Hydraulic cylinder and piston (plunger)

- The car frame connected directly to the piston, or connected by an extra frame and ropes

- Car guide rails

- Hydraulic power unit (tank, pump, motor, valve block, filter, and safety valve)

- Controller to coordinate the motor and valve actions

- Travel limit switches and buffers in the pit

Depending on the design, the cylinder can be installed in a drilled hole below the shaft (direct-acting) or placed beside the shaft (holeless or roped hydraulic).

How a Hydraulic Elevator Works

To move the car up, the controller starts the motor on the power unit. The pump draws oil from the tank and pushes it through the valve block into the cylinder. As oil fills the space under the piston, pressure rises. Since oil is almost incompressible, this pressure pushes the piston up. The car (connected to the piston or a frame driven by the piston) rises along the guide rails.

The up speed depends on pump flow and the piston’s effective area. In basic systems, the speed is nearly constant for most of the travel. In more advanced designs, variable-speed pump motors and proportional control valves control acceleration and deceleration to improve ride comfort.

To move the car down, the motor stops. The weight of the car and piston pushes on the oil in the cylinder. The controller opens one or more down valves in the valve block. Oil flows back to the tank through a calibrated opening that controls flow rate. The car goes down by gravity, while the hydraulic circuit controls speed. Accurate stopping at each landing is done by precise valve control, coordinated with position feedback from switches or encoders.

In a roped hydraulic system, the piston moves a pulley or frame connected to ropes. The rope path makes car travel longer than piston travel (for example, 2:1). This allows a shorter cylinder to give a longer travel, but it adds more moving parts and adds extra rope safety concerns.

Safety Features of a Hydraulic Elevator

Hydraulic elevators use safety features through the hydraulic circuit and mechanical devices:

-

A pressure relief valve is installed near the cylinder inlet. It watches the flow from the cylinder back to the tank. If a pipe breaks or a fitting fails and the flow suddenly goes above a set limit, the valve closes automatically. This limits down speed and prevents fast uncontrolled descent.

-

A check valve prevents oil from flowing back to the tank when the pump is not running. This helps prevent the car from drifting down due to internal leakage.

-

A pressure relief valve protects the system from over-pressure. When pressure goes above a safe limit, it opens and sends oil back to the tank.

-

In roped hydraulic systems, an overspeed governor and safety gear can be installed, similar to traction elevators, to clamp the car onto the rails during overspeed or uncontrolled movement.

-

Limit switches define the allowed travel range, and buffers in the pit absorb energy if the car reaches the bottom at low speed.

These features work together so that even if hydraulic parts fail, the car stays still or stops in a controlled way.

Special Setups: Direct-Acting, Holeless, and Roped

A direct-acting hydraulic elevator puts the cylinder under the car. To increase travel height, the cylinder must be long enough, which may require drilling a deep hole. But this is not always possible or acceptable, especially with poor geology or environmental limits.

A holeless hydraulic design avoids deep drilling by placing the cylinder beside the shaft. The piston pushes a cantilever-style car frame directly. Travel is limited by the real cylinder length and side loads on the piston.

A roped hydraulic system uses a shorter cylinder and steel ropes to multiply movement, so it can reach longer travel without deep digging. The cylinder stroke is shorter than the car travel, and the rope routing sets the mechanical ratio. These systems need extra parts like rope anchors, pulleys, and rope slack monitoring devices, but they can reduce civil construction work in the shaft.

Screw Drive, Chain Drive, and Other Home Elevators

In homes and small buildings, home elevators and platform lifts often use compact drive systems for short travel and narrow shafts. Their mechanical layout is different from traction and hydraulic elevators, but the structure is the same: a guided car, a drive system that turns motor rotation into vertical movement, and safety devices that control and limit that movement.

Main Parts of a Home Elevator

Designs vary, but typical elements include:

- A car or platform frame guided by rails or a mast

- A drive system (screw-and-nut, chain-and-sprocket, drum-and-rope, or pneumatic system)

- A motor and brake integrated with the drive unit

- A controller, and (if needed) a small drive inverter

- A door system with interlocks

- Safety devices matched to the mechanism (overspeed protection, gap detection, mechanical locks)

The guide structure can be a self-supporting shaft, a steel mast, or rails fixed directly to the building wall.

How a Home Elevator Works

In a screw-drive system, a vertical screw is fixed to the structure, and a nut moves along the screw. The car connects to the nut or a frame connected to it. When the motor turns the screw or the nut, the thread shape turns rotation into straight-line movement, lifting or lowering the car. The pitch and thread shape set the mechanical advantage and speed. Some screw systems also lock automatically when the motor stops, in addition to having a brake on the motor shaft.

In a chain-drive system, a roller chain runs around a drive sprocket powered by the motor. The moving part of the chain connects to the car or lift frame. When the motor turns the sprocket, the chain moves and pulls the car along the guide rails. Tensioners and guides keep the chain properly tight and aligned.

In a drum system, steel rope wraps on a drum and is paid out from the drum. The drum is driven by a motor and brake. As the drum turns, the rope length on the car side changes, moving the car. The number of wraps, drum diameter, and rope size set the movement behavior.

A pneumatic or vacuum lift works by air pressure difference above and below the car inside a tube. Pumps and valves control airflow, and mechanical locks hold the car at a floor. Even though the drive principle is different, the control tasks — start, stop, and level — are basically the same.

Safety Features of a Home Elevator

No matter the drive type, code-compliant home elevators and platform lifts include common safety ideas:

-

Door interlocks stop movement if the doors are not closed and locked.

-

If uncontrolled movement is detected, devices like overspeed governors, safety gears, or other braking systems act.

-

Slack chain or slack rope switches detect loss of tension in chain or rope systems and open the safety circuit.

-

Mechanical locking devices hold the car at a floor, especially in pneumatic systems.

-

For power loss or control failure, emergency lowering procedures and manual rescue tools are provided.

The safety chain in these systems is simpler than in large passenger elevators, but it must still make sure movement happens only when all required conditions are met, and failures lead to a safe state.

Special Considerations for Home Use

Home lifts and platform lifts are often installed in existing buildings with limited structure strength and space. This means the drive system must be compact, work with the existing power supply, and maintenance ease must be planned from the start.

For users and designers, it is not enough to only focus on the drive name in ads (“screw drive,” “hydraulic drive,” “chain drive”). You must check if it meets the right home elevator standards, understand how the mechanism prevents overspeed and uncontrolled movement, and make sure long-term maintenance support is available.

Summary Comparison

To make it easier to understand, the main elevator types can be roughly compared as follows:

| Type | Typical travel / use | Main lifting mechanism | Main features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traction | Mid- to high-rise | Motor drives the traction sheave, ropes, and counterweight | Wide speed range, high efficiency, MR or MRL |

| Hydraulic | Low-rise | Cylinder and piston, pump and valves | Simple shaft headroom, slower speed, needs an oil/lubrication system |

| Screw / chain / home | Short travel, residential | Nut, chain, drum, or pneumatic system | Compact shaft, low speed, many configurations |

This structure—main parts, working principle, safety functions, and special configurations—can be used in a consistent way for any new or hybrid design, to check if it fits a specific project.

What happens to an elevator during a power outage, fire, or other abnormal situations?

Besides how an elevator works in normal operation, are you also curious what happens in special situations? Next, let’s look at what an elevator will do during a power outage, fire, and other cases.

Power outage

When a power failure happens, the main power for the hoisting machine and the controller will be cut off.

Once the power is off, because the coil loses power, the brake of the hoisting machine will activate automatically. The car is held in place by the brake and the traction system.

Also, many modern elevators have an Automatic Rescue Device (ARD). ARD uses a battery or backup power to supply the controller, and moves the car at low speed to the nearest floor, so the doors can open and passengers can get out.

If ARD is not installed, the elevator car will stay stopped in the hoistway until power returns or trained staff rescue people.

Fire

When a fire happens, passenger elevator operation is limited by building codes and the building fire alarm system.

After the fire alarm is triggered, elevators usually enter fire recall mode. They finish the current trip, skip registered calls, return to the assigned recall floor (usually the main entrance or lobby), open the doors, and then stop serving normal passengers.

The goal is to stop people from using elevators to escape during a fire, because smoke, high heat, or water can affect the hoistway and equipment.

Special fire elevators or firefighter elevators have extra protection, such as fire doors, protected hoistways, and an independent power supply. They are only for the fire department, and not open to the public.

Elevator fire door

Earthquake

For earthquakes or other special cases, especially in areas with frequent earthquakes, extra sensors or seismometers can be added into the elevator system before installation.

Once triggered, these devices can tell the elevator to stop at the nearest floor and open the doors, then stop running until inspection is finished. The exact behavior depends on local standards and the building design.

Why some elevators run smoothly and quietly (and some do not)

When riding an elevator, vibration and noise are the most direct feeling. Passengers can quickly judge if the elevator is good or not from this. So why do some elevators run smoothly and quietly, while others do not? The main reasons are below:

Design and component quality

Ride comfort first depends on the design of motion control. A well-tuned VVVF drive and controller will choose proper acceleration and deceleration values based on the building type and use pattern. The speed curve is optimized to avoid sudden changes in acceleration, or it will feel jerky. The more accurately the control system coordinates motor torque, car weight, and encoder feedback, the smoother the ride will be.

Installation quality

Even the best elevator setup can be ruined by poor installation. Good installation must align the elevator guide rails within strict tolerances, to prevent side vibration.

The car frame, rollers or sliding blocks, and the counterweight also need correct sizing and installation, to avoid large gaps or misalignment.

If the guide rails are not vertical, the fasteners are loose, or the pit and overhead structure are built poorly, vibration and noise will pass into the cabin.

Maintenance and aging

Maintenance strongly affects the service life of the equipment. Even a high-quality elevator system will lose performance if lubrication is not enough, worn parts are not replaced in time, or checks and adjustments are not done regularly.

On the other hand, regular preventive maintenance helps keep noise, vibration, and leveling accuracy within acceptable ranges, and extends the system life.

A well-maintained elevator, even if it is not brand new, can still provide a smooth and quiet ride. But an elevator with poor maintenance, even if it started with good quality, will eventually become rough, uneven, and unreliable.

If you are choosing an elevator: what factors really matter?

If you are a building owner, developer, or someone evaluating elevator options, understanding how elevators work helps you ask better questions. Here are the most important parts in real projects.

Safety

Safety features should be seen as non-negotiable.

This includes a standards-compliant overspeed governor and safety gear, a machine brake designed to fail safely, effective door interlocks, and door protection using a light curtain or an equivalent device.

It also includes a reliable emergency communication system, and an automatic rescue device for power loss when needed. Checking compliance with recognized standards and local codes is the first step.

Capacity, speed, and traffic

Passenger flow and capacity analysis is another key part. The elevator rated load, car size, quantity, and rated speed should match the expected passenger flow and building function.

A system with not enough capacity will cause long waiting time and overcrowding. These quickly turn into operating problems and complaints.

Ride comfort and noise

Besides basic safety, ride comfort and noise level also deserve attention.

Technical documents can list rated speed, acceleration, leveling accuracy, and noise target values, but site conditions and installation quality are also important.

In practice, checking the supplier’s reference projects, and trying their installation in similar buildings when possible, can give valuable information.

Maintenance and long-term support

Maintenance and after-sales service decide long-term reliability and total cost of ownership.

Spare parts supply, fault response time, and technician skill level directly affect uptime and user satisfaction.

If maintenance support is weak, even a low initial price may be offset by high life-cycle cost.

FAQ

Finally, here are clear answers to some questions people often think about but rarely ask in public.

Q1: If the elevator ropes break, will the elevator free-fall?

In a properly designed and well-maintained traction elevator, the chance of this happening is extremely low. Elevators use multiple steel wire ropes with a high safety factor, plus an independent overspeed governor and safety gear system. If the car moves out of control, this system will lock the car firmly onto the rails. Modern elevators are designed to prevent uncontrolled downward movement, not only react after a fall.

Q2: What happens if I jump inside a falling elevator?

This is a common misunderstanding. From an engineering point of view, jumping at the last moment will not significantly change the impact force during an uncontrolled fall. The right approach is prevention—and modern elevators are designed for that, with the safety devices described above. Passengers should not try any dangerous actions; they should use the elevator normally and report any abnormal situation to building management.

Q3: Is it OK to overload the elevator a little, just once?

No. The rated load is calculated based on structural strength, the suspension system, braking ability, and machine performance. Repeated or serious overload can cause:

-

Triggering the protection system and stopping the elevator

-

Faster wear of parts

-

In extreme cases, safety can be harmed.

If the elevator often reaches its passenger limit, the real solution is better traffic planning or a higher-capacity system, not “pushing the limit”.

Q4: Why do some elevator doors close so fast?

Door closing speed is set by installers or the maintenance team based on standards, use type, and building needs. If the speed is too fast:

-

This setting may prioritize traffic flow, but it can feel uncomfortable.

-

If someone is detected at the doorway, the door sensors should still prevent contact.

If users often feel rushed or unsafe, the building owner can ask the service provider to adjust door open time within allowed limits.

Q5: Why can’t I use the elevator during a fire alarm?

During a fire, thick smoke, high heat, and unstable power can make normal elevator operation unsafe and not good for evacuation. The hoistway may become a path for smoke to spread, and the area near the fire floor can be very dangerous. So normal elevators are programmed to return to a safe floor and stop when the fire alarm sounds. Only specially designed fire elevators can be used under control by trained firefighters.

Q6: Are home elevators as safe as commercial elevators?

A certified home elevator made by a reputable manufacturer, installed to standard and maintained regularly, follows similar safety principles: controlled drive, door interlocks, emergency communication, and protection against uncontrolled movement. However, home elevator use patterns, drive systems, and the regulatory framework are often different, so these points are very important:

-

Please confirm it meets the home elevator standards used in your country/region.

-

Make sure the installer and service provider are experienced and reliable.

-

Treat a home elevator as critical equipment, not a decoration.

Which type of elevator is right for you?

Yes, you can easily find the perfect elevator, but it depends on your specific needs. Ask yourself:

-

What kind of riding experience do I want?

-

Do I need a fast, low-cost solution, or a long-term solution?

-

How much capacity do I really need?

-

Does my building need better energy efficiency?

Once you know what matters most for your space, here is a simple guide to help you choose the right elevator:

| Standard | Home Lift / Hydraulic Elevator | Traction Elevator |

|---|---|---|

| Ride Quality | Quieter and smoother, ideal for smaller spaces or homes. | Faster and more efficient, ideal for high-traffic buildings. |

| Best For | Residential use or smaller spaces. | Commercial spaces or high-rise buildings with larger capacity. |

| Capacity | Smaller capacity, designed for personal use. | Higher capacity, handles larger loads and more passengers. |

| Energy Efficiency | Simple design, more energy-efficient for smaller buildings. | Regenerative drives recycle energy, saving power, especially in high-rise buildings. |

| Speed | Slower speed, designed for low-rise buildings. | Faster speeds, suitable for high-rise buildings. |

| Installation Speed | Quick and easy to install in small spaces. | Longer installation time, requires more space and infrastructure. |

| Budget | More affordable, budget-friendly for small projects. | Higher upfront cost, more suitable for long-term investment. |

| Long-Term Efficiency | Efficient for residential use but less suitable for large traffic areas. | More efficient in the long run, especially in buildings with high foot traffic. |

Things you should pay attention to

To make the best decision, please consider these factors:

-

Passenger flow needs: Large buildings with more people will benefit from traction elevators.

-

Space limits: For smaller spaces, home elevators or modular systems may fit better.

-

Budget: If your budget is tight, home elevators are more cost-effective; but if you need a stronger solution, consider investing in traction elevators.

If you are not sure about your building’s needs, you can talk one-on-one with our experts based on your budget, available space, and people flow. BDFUJI can help you confirm which elevator is best for your project.